What’s all the drama about?

By Adam Goodbody

Chief of Staff

The decline of a vital subject.

Recent news has covered the worrying trend that significantly fewer students are studying performing arts, at both GCSEs and A-Level. This first decline is largely influenced by the now historic EBacc introduction which omits drama and music from the core mandatory curriculum.

I won’t recount the statistics of the decline as they are laid out better elsewhere. You can see them here:

The decline of drama at school prompts UK training drive for backstage work

The Guardian →

GCSE drama student numbers drop by 40% in 15 years

The Stage →

Number of A-level drama students plummets by 52% in 15 years

The Stage →

There are multiple knock-on effects to this decline, one of which is the shortage of skilled workers in the entertainment industry.

This is a phenomenon of lack, that initiatives like the National Theatre’s Skills Centre is trying to address. Backed by the Bank of America, the centre is trying to reimagine the craft of apprenticeship, increasingly lost, that allows young people to understand the skills and roles necessary for sustainable success in the theatre industry.

Whilst research suggests that as many as 75% of 18–25-year-olds want to work in the creative sectors, buildings in the theatre industry are having to post vacancies multiple times.

As Kate Varah, Co-Chief Executive & Executive Director of the National Theatre has recently said:

“The relationship between the creative industry and the education sector is at the centre of all this. It’s about ensuring there are sufficiently trained people to go forward, so we need teachers who can go into the expressive arts at GCSE level and start building the confidence for people to pursue a career in that area.”

The creative industries may be 1 of 8 pillars in the Government’s Industrial Strategy but those pipelines for talent clearly need attention.

Yet, there is a wider and even more concerning effect of declining performing arts study.

When I was at school, Drama GCSE and A-Level were the subjects in which I properly learned how to collaborate with others. The product of our collaboration was then assessed, formally, by the exam boards.

Whereas in other subjects, where collaboration featured as part of lessons and learning, but outcomes were solo, in Drama group efforts and solo efforts were essentially one and the same. This is akin to the working world, where millions of people work each day in groups, teams, and companies. The individual’s progress is tied to the collective.

It raises a wider ‘life learning’ that hits most people after university: outcomes up to degree level largely have a single and unitary cause: you. Yet, in life, your success is often contingent on those around you.

If your company does well, so do you. If your partner does well, so do you.

As spotty and stroppy teenagers, working together on a shared project wasn’t easy. In fact, it was often nigh on impossible: as a group of four preparing a play for A-Level, we had to deal with everyone learning in different ways and a spectrum of effort and ability.

Nothing can prepare you for professional life like that simulation.

In the discourse of skills education, there are multiple schools of thought, perhaps marked by the ‘explicit’ and ‘implicit’ methodologies.

Should students be taught how to collaborate explicitly or implicitly?

No one doubts the value and power of essential skills, more than ever now in a technologised world, but ways to do that are forever up for debate:

Should we name them?

What should we name them?

Should we assess them?

How do we assess them?

***

It is a mistake to think that studying Drama only qualifies you to work in the theatre.

If anything, it qualifies a young person for the multitude of jobs that call for “good team player” or “confident communicator” or “able to cohere and lead groups”.

I am not suggesting that we study certain subjects any less. Just that we study Drama more.

With that comes a narrative piece around encouraging young people into the subjects, doing our best to strategise about how to get more inspiring young people into teaching drama.

James Graham, the celebrate playwright recently wrote on this issue.

So, what could we do?

Breaking down the problem into constituent parts, we need to consider:

Wider Market Forces

The wider and prevailing narrative around Drama Education

The availability of creative jobs and pathways to employment

The status of Drama as a subject and curriculum reform, including its absence from the EBacc programme.

Capabilities of Schools

Do we have enough drama teachers?

Are Drama teachers being properly supported?

Is the Drama curriculum being taught effectively?

Strategic Alternatives

Should we be doing more to facilitate drama sessions and experiences for state funded schools outside the studied curriculum?

What is the role of Arts Council England and other funding bodies that support external institutions to engage young people in the creative arts?

Could we develop the responsibilities of drama schools (Conservatoires)?

In response to this scheme, a few ideas could be:

1.

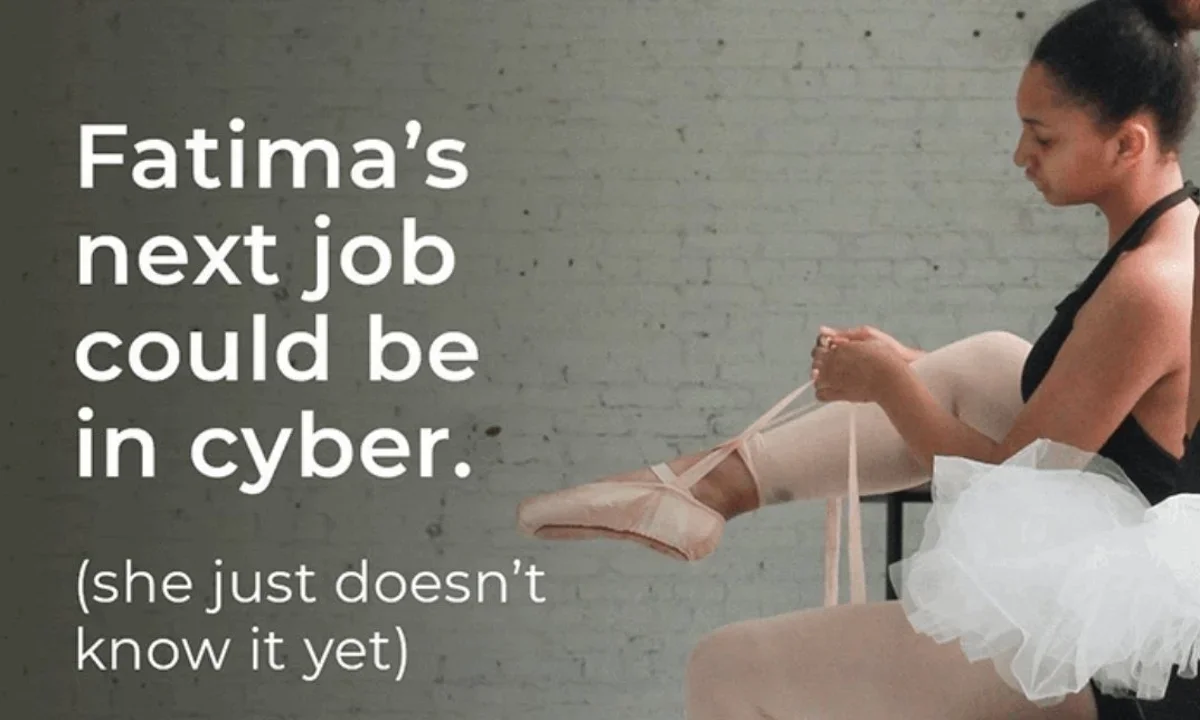

We need a Government sponsored national campaign to encourage young people into the performing arts and / or championing the importance of the performing arts in developing these skills. In some ways, it might look like the exact opposite of the infamous 2020 Government campaign below:

2.

The bold extension of (1) would be the addition of music & drama to the EBacc mandatory qualification.

You can see more about that idea and those creatives who have signed an open letter about it here.

An announcement on a full curriculum review is scheduled for Autumn 2025 with the Interim report having been published here. This a review led by Professor Becky Francis CBE.

3.

We need to think in more imaginative ways about how we attract drama teachers into the pipeline, perhaps exploring closer connections between Conservatoires and local schools across the U.K.

This to me is contingent on wider thinking about qualification requirements for teachers in marginalised subjects such as Music & Drama. Whilst I’m not advocating a relaxation in standards, the position and logic of the QTS feels thin in undersubscribed subjects.

***

If the government really wants to commit to creativity as one of their eight pillars, and more widely, to develop a pipeline of graduates with strong essential skills, we need to look again at Drama in a serious way.

We need to revitalise it.

Adam is Chief of Staff at Oppidan Education. He also runs Buzz Studios, a theatre and education collective that seeks to reimagine classic stories, and make them accessible to young people.